Finally, this is the chapter that educators and students have been patiently looking forward to – Music Composition with Mixcraft! Chapter 7 surveys concepts of music composition in the form of songwriting. For educators who do not boast a rich music background and are unfamiliar with songwriting, the song structure is dissected into several understandable components. Next, several approaches towards songwriting are explored using a number of popular song structures. Students are encouraged to adapt these structures during songwriting efforts. Finally, as a specific example exercise, a brief tutorial on loop-based composition with Mixcraft is provided. This concluding tutorial demonstrates how to create a simple, 12-bar blues song in minutes using just four loops.

WHAT’S IN A SONG?

Music is an intricate and multifaceted art form. As listeners, we learn to talk about and appreciate music from the perspective of the bystander. Often this form of discussion masks or trivializes the struggle of writing an original piece of music. However, undertaking the actual task of writing a song quickly reveals both the challenge and the difficulty of organizing notes and lyrics into a meaningful work of art. Before embarking on the journey of songwriting, educators and students need to know the basic structures of a song. Below is a breakdown of a prototypical song. Included with the definitions are ways that these concepts are reflected in Mixcraft. Educators may use this information to highlight the structural components of a song. Finally, it may be helpful for educators to accompany a lesson by having students listen to examples.

A song is simply a music composition that contains words and may be arranged to include musical instruments. The modern world is alive with song; nearly everywhere we go songs from all genres serenade us. Thus it should be easy, then, to engage students in a discussion of music favorites.

There will probably be a range of music style preferences to be debated over or agreed upon. Perhaps this discussion could then be nudged into a look at the history of song and the changes that have occurred as various song genres have evolved over the past decades and historical eras and new forms have been created. At this point, students should be primed to learn that all the diverse songs they have fiercely argued about have more in common than is readily apparent; and that these songs are linked by many of the same common core components that follow:

Melody: The prominent theme or “tune” on which a composition or song is based. A melody is a collection of individual notes that are perceived as a unit or as a whole phrase. Notes of the melody are usually selected from a musical scale – a set of notes related to a musical key – and often move in a step-wise fashion.

In Mixcraft:

Melodic Instrument Loops (e.g. Cello, Fiddle, Trumpet, Bagpipes, etc.)

Monophonic Virtual Instruments (e.g. Alien 303 Bass Synthesizer & Synth Lead – Hard/Soft virtual instruments)

Harmony: Contrastingly, harmony refers to notes that are played simultaneously. In popular music, harmony is often discussed in terms of chords (chords are comprisedof three to four notes stacked according to the interval of a 3rd) and their relativity to other chords (called “chord progressions”).

In Mixcraft:

Harmonic Instrument Loops (e.g. Choir, Guitar, Piano, Organ, etc.)

Polyphonic Virtual Instruments (Combo Organ Model F / V, Minimogue VA, Lounge Lizard Electric Piano, etc.)

Meter: Meter refers to the underlying pulse or “beat” of a song. Simple meters such as 4/4 have evenly-spaced beats while complex meters such as 7/8 have unevenly-spaced beats. These categories of meters are often culture-specific. American students are likely to be familiar with simple metrical times, while Balkan students might prefer complex meters. Thus, cultural and musical background may define which meter a student chooses for a song writing assignment.

In Mixcraft:

Time Signature

Rhythm: Rhythm refers to the temporal variation between note onsets. In other words, rhythm refers to the time or space between individual notes. In a metrical hierarchy, rhythm is subordinate to meter. Rhythmic events can occur on, between, or even off beats. Many different rhythms may coexist in a song.

In Mixcraft:

Drum or Percussion Loops (e.g. Tambourine, Shakers, Hip-Hop Drums, etc.)

Acoustica Studio Drums virtual instrument.

Timbre: Timbre refers to the “tone color” of an instrument. Timbre is a component notoriously difficult to define. It is, however, an easy concept to illustrate: imagine a piano player and flute player both playing the same note, for example, F#. The only perceived difference between the two instruments and the note produced is the quality or color of the instrument itself. The same could be said about the voices of two singers. Timbre is an important facet of music composition and is generally considered when arranging songs or when synthesizing sounds.

In Mixcraft:

Mixcraft Instrument Loops (i.e. varying classes of instruments)

Virtual Instruments, notably Mixcraft’s virtual synthesizer instruments

Tempo: The tempo defines the speed at which a song is to be performed. In Mixcraft, the tempo is defined in beats-per-minute (BPM) which determines the rate at which the software plays audio. From a compositional perspective, setting the tempo can drastically influence the perceived emotion of the song: slower tempos tend to be feltas “sadder” while faster tempos tend to be associated with joy or happiness. For educators and students used to traditional tempo terms, below is a list of their respective BPM values in Mixcraft:

Largo – very slow, (40–50 BPM)

Adagio – “at ease,” slow and steady (51–60 BPM)

Andante – moderately slow, at a walking pace (61–80 BPM)

Moderato – moderate (81–90 BPM)

Allegretto – moderately quick (91–104 BPM)

Allegro – fast (105–132 BPM)

Vivace – fast, lively (≈132 BPM)

Presto – very fast (168–177 BPM)

Prestissimo – extremely fast (178–208 BPM)

In Mixcraft:

Beats Per Minute (BPM).

Key: A musical key is a determined set of notes that is used in a particular composition. The key of a song has the name of its keynote (for example, a song may be in “C major”). Keys can be either major or minor, depending upon the tonal relationships between the notes. For students, the key is important for establishing a mood for the music. Major music tends to be perceived as happy, carefree, and uplifting. On the other hand, minor music is often described as somber, melancholy or bleak. Many of Mixcraft’s loops are labeled with their respective keys, making it easy to compile and experiment with loops from different libraries.

In Mixcraft:

Key

COMMON SONG SECTIONS

The structure of songs differs according to genre. Songs that are comprised of repetitive structures are referred to as strophic songs. In contrast, thorough-composed songs are linear but non- repetitive. Much of popular music uses the strophic form. These songs are comprised of smaller parts, or sections, that are strung together to create several minutes of music. Before attempting the composition of a popular piece, a student should understand the unique song sections usually found in strophic forms. Below is a brief overview of these common song sections:

Introduction: The introduction is a musical greeting which prepares or sets up the audience for the song experience that follows. Introductions are primarily instrumental sections that transition to the first verse. In popular music, introductions are kept relatively short – usually only a few measures long. However, some music genres and songs use extended instrumental introductions (see: Pink Floyd’s “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” or “Heart Of the Sunrise” by Yes). Students should ensure that their introductions do not sound disconnected or unrelated to the music in the first verse.

Verse: A good songwriter is a good storyteller. Verses are sections of songs reserved for the lyrics that provide the listener with a narrative. Between verses, lyrics tend to vary drastically, yet each subsequent verse remains related to the topic of the song and continues the story. Students should consider plotting the story of the song before writing lyrics. When discussing song structures, verses are referred to as the “A” section.

Chorus: The chorus is a repeated section of a song often referred to as “the hook.” Lyrically, the chorus might compliment or summarize the content of the verses. Lyrics rarely change between choruses (repetition is a powerful tool in songwriting). This section of the song is designed to be catchy and memorable and should stand out from the rest of the song. Choruses are referred to as the “B” section.

Bridge: True to its name, the bridge is a short section of a song that occurs after a chorus and before a verse, thus “bridging” these two sections. The bridge usually introduces new music and new lyrics and occurs only once. The bridge comes later in the song, usually after a 2nd or 3rd chorus. Bridges are referred to as the “C” section.

Example Song Structures: The above song sections can be arranged to form higher-level, complex musical structures. In most instances, the verse (or introduction) is the primary section that starts the song. Below are song structures that are widely prevalent in popular music. Adventurous students can create their own song structures and use these examples as starting points. As a reminder, verses are deemed the “A” section, choruses the “B” section, and the bridge the “C” section:

AABA (Verse-Verse-Chorus-Verse)

AAA (Verse-Verse-Verse)

ABAB (Verse-Chorus-Verse-Chorus)

ABABCAB (Verse-Chorus-Verse-Chorus-Bridge-Verse-Chorus)

ABACAB (The 1981 Genesis song... the song name actually comes from its Verse-Chorus-Verse-Bridge-Verse-Chorus form!)

Arrangement / Orchestration

Once a song is written, it needs to be arranged or orchestrated for a set of instruments. This process involves assigning an instrument to play a specified part. When arranging, it is important to consider the instruments available to the student or educator, the expectations of the audience, and the structural components of the music. For example, including a flute part might be a senseless decision if there is no a flute player to perform the part (of course you could always use Mixcraft’s virtual flute instruments or a flute loop in place of a performer). If the audience is expecting a particular kind of music, say electronic music, a rock song might not be an appropriate addition to the repertoire. Finally, be careful when choosing instruments for parts: designating a melody that is out of the playing range of a particular instrument is a common mistake among young songwriters and composers.

Music genres:

Classical: Strings (violins, violas, contrabass, cellos), Brass (Trumpets, FrenchHorns)

Jazz: Piano, Trumpet, Upright/Electric Bass, Guitar, Percussion Instruments Rock: Guitar, Electric Bass, Drums, Synthesizer, Piano, Organ, Percussion Electronic: Drum Samples, Synthesizer, Field Recordings

Indian: Sitar, Tabla, Violins

Irish: Irish Whistle, Bodhran, Fiddle, Harp, Uilleann Pipes

AN APPROACH TO MAKING MUSIC WITH MIXCRAFT: LOOP-BASED MUSIC

When it comes to music composition, there is no “correct” method. In Mixcraft, this is certainly illustrated by the unlimited potential held within the software: Mixcraft has no limit on the number of audio or virtual instrument tracks that can be active during a session. Theoretically, students could add an infinite number of tracks to their composition. The only limit is the CPU capacity of the computer on which Mixcraft is installed. Various approaches towards music composition can be taken within Mixcraft, including using Mixcraft’s built-in virtual instruments or by recording live music into the software. However what may contribute the most to Mixcraft’s unique identity as a compositional tool is its extensive loop library.

Loop-based music is a form of music that is constructed entirely from loops. In the classroom, loop-based music is a great compositional strategy to use with students of all ages. Younger students, with little or no knowledge of music, can create songs simply by arranging loops. Older students will find that loops can compliment recordings and are great tools for producing specific types of music such as dub-step or hip-hop. Finally, educators will appreciate both the affordability of loops (they come free with Mixcraft and require no additional music equipment) and the convenience of using loops to prepare lesson plans. Below are some advantages and disadvantages of loop-based music:

Benefits of using loops in the classroom:

High-quality audio

Already edited, easy to arrange

Comprehensive loop library that covers all genres

Students do not have to perform the music (i.e. loops are ideal for non-musicians)

Limits of using loops in the classroom:

Editing is limited by music key and tempo

Constrained to the melodies or harmonies in the loop

Can result in extremely repetitive music

TUTORIAL

COMPOSING AN 8- OR 12-BAR SONG USING LOOPS

The 8- and 12-bar song formats are common chord progressions played in 4/4 time that are used in blues music. The progressions consist of three chords (I – V – IV chords) that alternate over the course of 8 or 12 bars (one bar is equal to 4 beats). Both structures are ideal for students who are unfamiliar with harmonic progressions. Though multiple versions of a basic 8 or 12-bar structure exist, it is recommend to start with the original blues forms. Below are the standard

8-bar and 12-bar blues:

Chord # | I (1) | V (2) | IV (3) | IV (4) | I (5) | V/IV (6) | I (7) | V (8) |

In the key of C Major | C | G | F | F | C | G/F | C | G |

The 8-bar format

Chord # | I (1) | I (2) | I (3) | I (4) | IV (5) | IV (6) | I (7) | I (8) | V (9) | V (10) | I (11) | I (12) |

In the key of C Major | C | C | C | C | F | F | C | C | G | G | C | C |

The 12-bar format

In the brief tutorial that follows, Mixcraft’s blues loops will be used to create a 12-bar blues song. The libraries by Blues Ballad and Michael Bacich are excellent selections for high-quality blues loops.

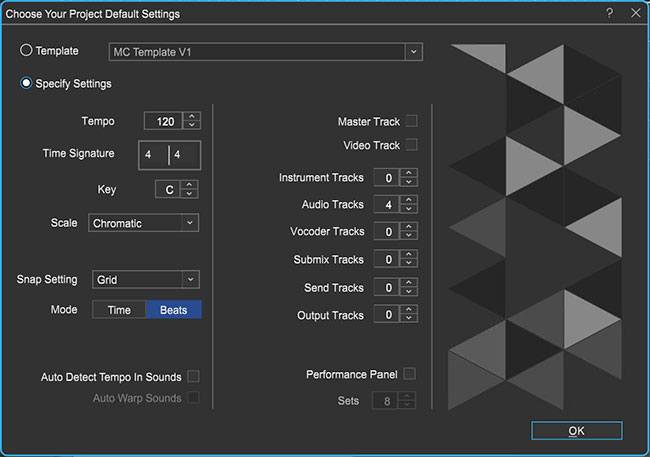

Open Mixcraft and use the New Project window to load a template with four audio tracks.

Set the audio tracks field to a value of four.

Set the audio tracks field to a value of four. Loop Library. Open the Loop Library by selecting the Library tab in the Tab Area (located in the lower left hand corner). Change the “Sort By” setting to “Style” and select “Blues” from the menu below. Only Mixcraft’s blues loops will now be displayed in the browser to the right.

Changing the “Sort By” setting to Style allows users to browse the Blues loops.

Changing the “Sort By” setting to Style allows users to browse the Blues loops.Creating the rhythm section. Start by creating a rhythm section consisting of rhythm guitar, piano, and bass. For the guitar loop, select the Rhythm Guitar 1 loop in G Major by Michael Bacich.

In the loop library browse or search to find the Rhythm Guitar 1 loop.

In the loop library browse or search to find the Rhythm Guitar 1 loop. Drag the loop onto a free audio track in Mixcraft’s Timeline. Mixcraft will prompt the user to change the project’s key. Select “yes.”

Adding Piano. Next, select the Piano RH 1 loop in G major, again by Michael Bacich and drag the loop onto the Timeline. Align it with the Rhythm Guitar 1 loop.

Adding Bass. Select the Bass 2 loop in G major by Michael Bacich. Repeat the process of adding the loop to the Timeline.

Finishing the blues with drums. Finally, add the Drums 2 loop by Blues Ballad. Drag the loop onto a free audio track on the Timeline.

Looping loops. Things are starting to get a bit loopy(!), but in order to finish the 12-bar blues several of the blues loops must be extended:

Start with the drum loop. Click the circle with a “+” to extend the loop another bar. Keep looping the audio region until the drums are playing throughout the song.

The circle with the “+” loops the audio region.

The circle with the “+” loops the audio region.Next, loop the guitar, bass and piano for another 12 bars. The song should now be 24 bars long.

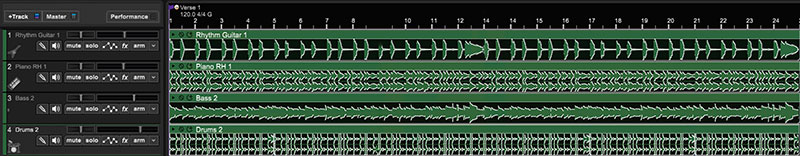

After all the looping is completed, Mixcraft’s Timeline should appear as follows:

This 12-bar blues piece consisting of guitar, piano, bass, and drums has been looped to 24 bars.

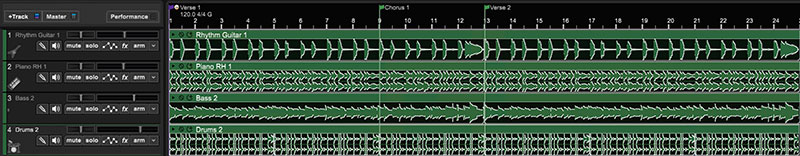

This 12-bar blues piece consisting of guitar, piano, bass, and drums has been looped to 24 bars.Copying and pasting large structures: Once a verse or chorus has been created, users can highlight the verse or chorus, copy the selection, and then paste the verse or chorus on the Timeline to create a duplication. This workflow is helpful in creating complete songs with a minimal amount of clicks.

In this screen shot, Verse 1 and Verse 2 are identical. Verse 2 was created by copying and pasting the loops from Verse 1 onto the Timeline where Verse 2 is located following the chorus.

In this screen shot, Verse 1 and Verse 2 are identical. Verse 2 was created by copying and pasting the loops from Verse 1 onto the Timeline where Verse 2 is located following the chorus.

TRICK AND TIPS WITH LOOPS

In addition to performing the standard edits to loops and their respective audio regions, here are some tricks and tips that educators can use with loop-based music:

Changing the pitch of a loop: Users can change the key or the pitch of the loop in the Sound tab. Simply double-click on a loop or select the Sound tab in the Tab Area to open the window. Here, users can transpose the loop to a new key or adjust the loop’s pitch by semitones (half-steps).

With the pitch “steps” option selected, users can now modify the loop’s pitch by semitones.

With the pitch “steps” option selected, users can now modify the loop’s pitch by semitones.TIP: Changing a loop’s pitch is useful for creating chord progressions. For example, users can create a basic I-IV-V progression by semitones (IV = 5 semitones) (V = 7 semitones)

Placing Effect Plugins on loops: If students wish to add effect plugins to loops, they can begin by clicking the “FX” button on the corresponding audio track. This will open the effects browser.

Selecting the “FX” button on the Bass Guitar audio track will allow users to apply effects to the bass loops on that track.

Selecting the “FX” button on the Bass Guitar audio track will allow users to apply effects to the bass loops on that track.Creative approaches: Experimenting with loops can be a lot of fun but it is easy to mindlessly abuse their usability. Often, students hoping to create an interesting song will layer dozens of loops on the timeline. The end result is a convoluted mess in which the definition of each instrument is lost. Encourage students to remember the following when creating music with loops:

What is the “density” of the arrangement?

What is the “focus” of the track – is it a vocal track? Or a solo instrument? Leave space for the main attraction.

BEYOND LOOPS

Using loops is just one approach to making music with Mixcraft. Students can also use Mixcraft’s virtual instruments or record directly with acoustic and/or electronic instruments.